Paris, August 2nd, 2025

“A generation unbroken

in the ‘flat cap’ * we remain

alive to this day.” KB

…but still failing to produce democratic leaders.

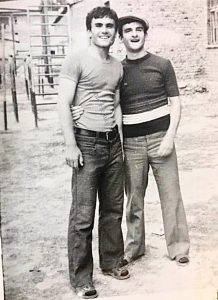

In the Albania of my youth, even silence wore the weight of ideology. The year was 1979. Each day moved like a rehearsed gesture, tightly regulated between the threat of punishment and the furtive longing to feel—if only for a breath—something different. In the midst of that rigid normalcy, a photograph was taken. Two boys smile unpretentiously at the camera, dressed in simple clothing, yet with a natural grace that slipped through the mesh of control.

To the right stands Arian, wearing a horizontally striped shirt and trousers just loose enough at the knees to avoid the dreaded label of “cowboy decadence.” But what truly unsettled the scene was perched on his head: an English flat cap, worn not with bravado, but with quiet certainty. It hadn’t been bought. It wasn’t on offer. It held no place on any approved list. He had found it in an old trunk, without label or price—as though the wind had brought it from another world.

I like to believe that Arian had found more than an object. He had found a loophole. “Nowhere,” he must have thought, “is it written that a flat cap is forbidden.”

Captured on the eve of the final secondary school exams, Janaq Kilica Gymnasium, Albania, 1979.

But in Fier, at that time, nothing was merely aesthetic. A flat cap was a signal. A tilt in the wrong direction. A potential virus of nonconformity. For those charged with maintaining “order”, that modest accessory whispered of bourgeois vanity, a threat to the regime’s ideal of the New Socialist Man. Their message traveled swiftly to the intended ear:

— “What is that cap your son is wearing?”

Arian gave no explanation: ” E vure disa ditë, pastaj e hoqa, nuk e di ? shikimet vëngër, një vetull e ngritur…”(…)

Perhaps out of pride. Or perhaps because there was no point explaining in a world deaf to anything but obedience. A few days later, the flat cap disappeared. Not the defiance—only its visible form. It was likely folded away, slipped quietly into a drawer, alongside dreams that had never been granted permission to circulate.

But the photograph remained. So did the smile. And the memory—clear, stubborn, quietly luminous—of a boy who wore something that did not belong because he understood that belonging itself had become dangerous. In a land where equality often meant erasure, that small piece of cloth carried entire shades of forbidden meaning: irony, elegance, whim, will.

Today, I look at that image and see not only the past, but a thin thread of continuity. A gesture not extinguished.

“A generation unbroken/in the flat cap we remain/alive to this day.” KB

See Serie / Catalogue of Forbidden Objects under the Communist Regime

Copyright KBP

© This article may not be republished, even if credit is given to @klarabudapost.

© The photo is protected by copyright and may not be reused: Left to right: Ledio Pasha and Arjan Nikaj.

* ‘flat cap’ as methaphore…

#Albania1979 #DictatorshipMemories #ForbiddenStyle #YouthAndResistance #FlatCapStory #CommunistEra #PersonalHistory #FierChronicles #MemoryAndIdentity #KlaraBudaPost