Paris, Janvier 25, 2022

About social-realisme in people’s democracy, contemplative poems…

Czesław Miłosz’s thoughts on the destruction of lyricism in socialist realism is a profound critique of how authoritarian regimes can influence and even destroy individual artistic expression. Miłosz, a Polish poet and thinker, observed firsthand the impacts of political oppression on literature during the Stalinist era in Eastern Europe.

In this context, socialist realism was an artistic style promoted by communist regimes, especially under Stalin, which aimed to promote an idealized vision of the proletariat and class struggle. Art was meant to be accessible and understandable to the people, while highlighting the values and objectives of the Communist Party. This approach had a didactic and propagandistic scope, leaving little room for personal expression or the exploration of more nuanced or ambivalent themes.

Miłosz criticizes this limitation by pointing out that under such a regime, art cannot simply adapt to external guidelines without losing its essence. Lyricism, which in poetry can be seen as the expression of deep and personal feelings, as well as the use of beautiful language to explore complex truths, is particularly vulnerable. Under socialist realism, poets risked losing not only the freedom to compose according to their inspiration but also their very ability to perceive and express reality other than through the prisms imposed by the regime.

Thus, Miłosz expresses a dual loss: that of artistic freedom and the very ability to conceive of art as a means of personal and spiritual exploration. This leads to a uniformity that harms not only artists but society as a whole, as it loses access to forms of expression that allow for essential reflection and questioning.

Contemplative poems, such Rilke’s poems, could never appear in a people’s democracy, not only because it would be difficult to publish them, but because the writer’s impulse to write them would be destroyed at its very root.

“We are not concerned with the question of how one finds the courage to oppose the majority. In stead we are concerned with a much more poignant question: can one write well outside that one real stream whose vitality springs from its harmony with historical laws and the dynamics of reality? Rilke’s poems may be very good, but if they are, that means there must have been some reason for them in his day. Contemplative poems, such as his, could never appear in a people’s democracy, not only because it would be difficult to publish them, but because the writer’s impulse to write them would be destroyed at its very root.”*

The passage from “The Captive Mind” by Czesław Miłosz delves into the complex relationship between artistic creation and societal structures, particularly under repressive regimes. Miłosz presents a critical exploration of whether true artistry can exist independently of the dominant cultural or political currents that are in accord with the historical and social dynamics of the time.

He begins by dismissing the idea of individual courage against the majority as a primary concern. Instead, he poses a more profound inquiry: whether one can still produce quality writing when detached from the main “stream” whose vitality is derived from aligning with historical laws and the dynamics of reality. This “stream” symbolizes the prevailing ideological and cultural forces that shape artistic expression.

Using Rilke as an example, Miłosz points out that if Rilke’s poems are considered good, it is because they were relevant and resonant during his time. They emerged from and spoke to the cultural and societal context of his era, which allowed them to flourish. Miłosz contrasts this with the hypothetical scenario of a “people’s democracy” (a euphemism for communist regimes), where such contemplative, introspective poetry would not only face practical barriers to publication but would also confront a more existential threat. Under such regimes, the very impulse to create art that does not conform to the state-prescribed doctrine or serve the state’s purposes would be stifled or eradicated.

This passage highlights a crucial theme in Miłosz’s work: the idea that totalitarian systems don’t merely censor art but seek to reshape the very instincts and desires that give rise to artistic expression. This reshaping is done to ensure that all creative output supports the state’s goals and reinforces its ideology, thereby eliminating the personal, introspective quality that defines much of what is considered great art in freer societies.

Miłosz’s commentary is not only a critique of censorship and state control but also a lament for the loss of internal freedom that enables artists to explore and express genuine human emotions and thoughts. His insights into how political environments affect artistic creativity remain relevant, prompting reflections on the conditions under which art is produced today and how those conditions influence the authenticity and vitality of creative works.

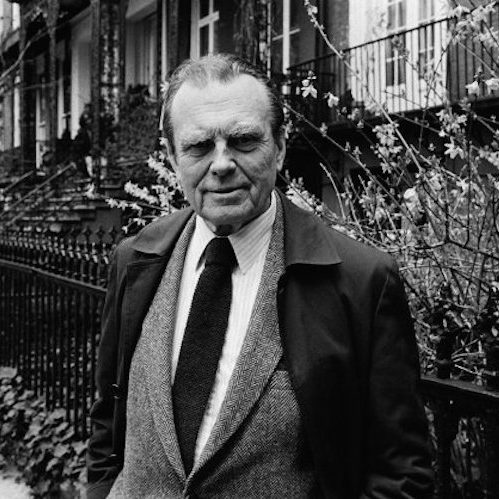

Czesław Miłosz was a Polish-American poet, prose writer, translator, and diplomat. Regarded as one of the great poets of the 20th century, he won the 1980 Nobel Prize in Literature. In its citation, the Swedish Academy called Miłosz a writer who “voices man’s exposed condition in a world of severe conflicts”.

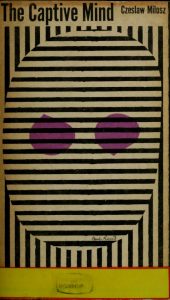

*CM, p 24. The Captive Mind.

The Captive Mind was written in Paris (1951-1953) soon after the author’s defection from Stalinist Poland in 1951.

Nobel Prize Czeslaw Milosz (30 June 1911-14 August 2004)

Nobel Prize Czeslaw Milosz (30 June 1911-14 August 2004)