I. Blue as a Critical Moment in Modern Painting

In the history of modern painting, blue is never a neutral color. It appears at specific moments when painting turns away from narrative, anecdote, and immediate seduction in order to question states of consciousness, memory, or withdrawal.

The Blue Period of Pablo Picasso (1901–1904) constitutes a decisive first landmark. Blue is associated there with poverty, solitude, and exclusion. Female figures often appear in mourning, frozen in a suspended temporality. Blue acts as a regulator of the gaze, imposing a moral and emotional distance.

In the work of Odilon Redon, blue—particularly in his pastel female profiles—becomes a mental space. The woman is no longer described but suggested; she hovers between apparition and disappearance. Blue functions as a medium of interiority rather than of flesh.

With Henri Matisse, especially in Woman in Blue (1907), blue detaches itself from melancholy to become an autonomous plastic structure. The female figure is constructed by color itself. Blue no longer expresses a psychological state but establishes a pictorial harmony.

Finally, in Marc Chagall, blue becomes a site of affective and spiritual memory. The blue woman is a guardian of remembrance, a figure of interiorized love and dream.

In all these cases, the woman in blue is not a decorative motif; she is the support of a shift in meaning, from narration toward thought.

II. The Early Women in Blue by Daut Berisha: Memory and Interiority

Trained at the Academy of Fine Arts in Belgrade, within the context of former Yugoslavia, and later settling in Paris in the 1970s, Daut Berisha inherits this modern tradition while recontextualizing it historically.

In his early women in blue, the figure remains identifiable, sometimes melancholic. The body is present; the face expressive. Blue functions as an enveloping atmosphere linked to memory, silence, and historical aftermath. These works belong to a still-lyrical painting, in which color accompanies the figure.

The feminine appears as a site of restraint: neither an object of desire nor a heroic figure. The choice of blue already signals a distance from red—the color of passion, violence, and blood—too heavily charged in a post-totalitarian context.

III. Toward a Structuring Blue: Woman as a Field of Thought

In a second phase, Berisha radicalizes his pictorial language. The woman in blue is no longer simply surrounded by color; she is traversed by it.

Contours are simplified, volumes flattened, and line becomes structural. Blue ceases to be atmospheric and becomes an organizer of space. The female figure begins to detach itself from explicit psychology and becomes a site of construction.

This evolution brings Berisha closer to certain late modern explorations, notably those of Mark Rothko—not through abstraction, but through the idea that color alone can carry intellectual intensity.

IV. Woman in Blue (Late Work): Condensation and Fulfillment

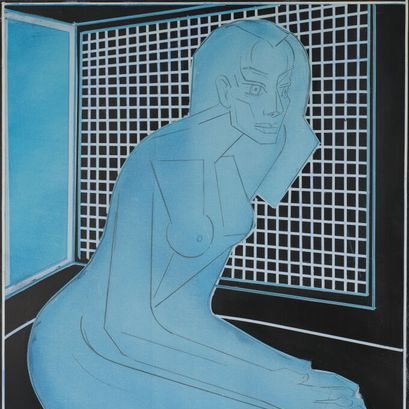

The painting you presented clearly belongs to this phase of condensation.

The figure is geometrized, almost architectural. Internal lines resemble a diagram, a mapping of the body. The open arms are neither expressive nor narrative; they stabilize the composition. The face is fragmented—not to express crisis, but to affirm construction.

Here, blue is no longer symbol or emotion. It is mental structure. Background and figure merge. There is no longer a hierarchy between subject and space.

This work should not be placed at the beginning of the series, but at its conclusion. It does not repeat the motif of the woman in blue; it completes it.

At this stage, the choice of blue definitively excludes red. Red would be too dramatic, too narrative, too historically charged. Blue allows for duration, stability, and thought without emphasis.

In the history of modern painting, the woman in blue appears whenever painting renounces seduction in order to think.

Berisha e Kuqe belongs to this lineage, yet he displaces it toward a contemporary problem: thinking after political silence.

His women in blue evolve:

-

from memory to structure,

-

from interiority to construction,

-

from the body to thought.

In his late work, the woman becomes a form of consciousness.

Blue is no longer a chosen color; it is the very site where painting thinks.

La Femme en bleu, vers 1980–1990

Technique mixte sur toile

La Femme en bleu, vers 1980–1990

Technique mixte sur toile